Picture a single mother in Ohio, juggling a full-time job while caring for her toddler and an aging parent. One phone call, her daycare shutting down unexpectedly, sends her scrambling and puts her job at risk. Meanwhile, a home health aide in New York, an immigrant on a temporary visa, lies awake at night worrying that a policy change could strip her work authorization and leave her elderly clients without care. Thousands of miles away, in a remote village in Delta, Nigeria, a grandmother tends to children left behind as their parents migrate to find work, even as drought and conflict strain the community’s ability to cope. These disparate scenes share a common thread: a global care system under profound strain. The instability of caregiving – for children, elders, and vulnerable family members – has become a silent emergency, exacerbated by rising uncertainties like authoritarianism, war, migration crises, and demographic shifts. The human toll is heartbreaking, and as we’ll explore, the economic costs are staggering. In this narrative analysis, we blend personal stories with data to illuminate how care instability is rippling through economies and societies – and why urgent, coordinated action is needed.

An Aging America’s Care Crunch

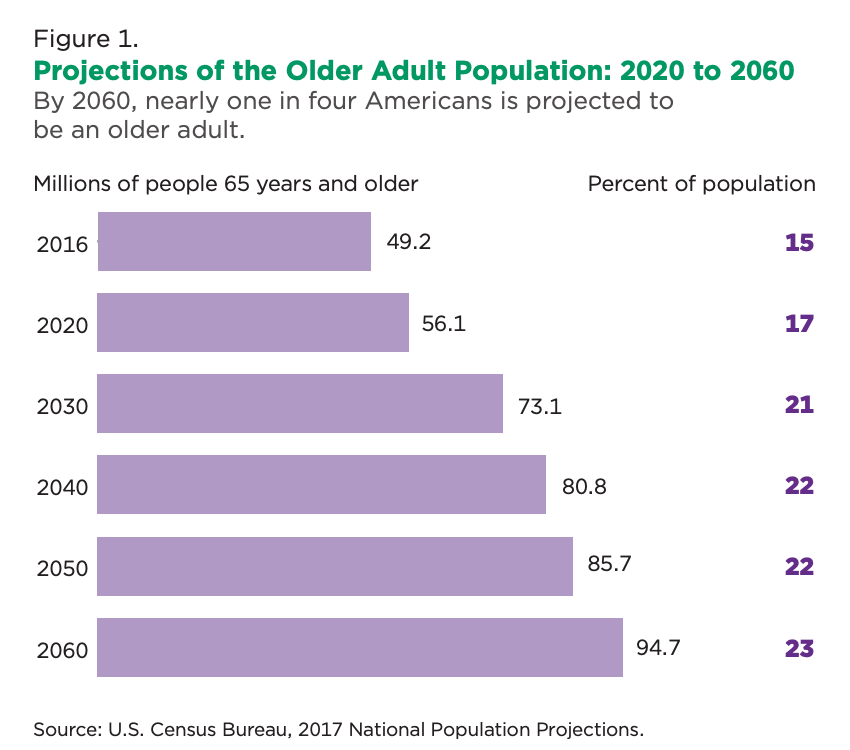

In the United States, immigrant caregivers are often the unseen backbone of eldercare and home health services. The United States is hurtling into an age demographic revolution that is testing the limits of its caregiving systems. By 2030, all Baby Boomers will be over 65, meaning one in every five Americans will be of retirement age. Just a few years later, in 2034, older adults are projected to outnumber children for the first time in U.S. history. This seismic shift portends a surging demand for caregiving – and a strain on families and services unlike any before.

Today, there are roughly 73 million Americans over 65 (projected for 2030) comprising more than one-fifth of the population . Many of these older adults will require assistance: an estimated 70% of 65-year-olds will need some long-term care in their remaining years . Yet the supply of care workers and support systems is not keeping pace. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics anticipates the direct care workforce (home aides, nursing assistants, personal care aides) will need to grow by an additional 865,000 workers between 2022 and 2032 – a growth rate among the fastest of any occupation . Even so, that increase is likely insufficient to meet the exploding demand, as America’s ratio of working-age adults to seniors continues to fall (from 4.2 in 2000 to about 2.9 today) .

The caregiving shortfall is already being felt in American communities. We see it in the staffing crises at nursing homes and home care agencies, where job vacancy rates are high and turnover is rampant. In home care, nearly two-thirds of workers leave their jobs within the first year due to low pay, burnout, and difficult conditions . Wages for care aides remain stubbornly low – the median pay is only around $34,000–$38,000 a year for these physically and emotionally demanding roles . With such wages, many caregivers can barely support their own families. Not surprisingly, providers struggle to recruit and retain staff, leading to a chronic workforce gap even as needs grow. “The sector has been struggling to retain the workforce outside of immigration,” says Jeanne Batalova of the Migration Policy Institute, warning that any hit to the immigrant workforce would be felt “very quickly” in lost services.

Indeed, immigrant workers have become the backbone of the U.S. care economy, filling critical roles in child care, home health, and eldercare. Immigrants make up about 19% of the overall U.S. labor force but a far higher share of direct care workers . In long-term care services, immigrant women and men comprise roughly 28% of the direct care workforce as of 2023 (up from 24% in 2018) . In certain sectors, the reliance is even more pronounced: more than 40% of home health aides and nearly 30% of personal care aides in the U.S. are foreign-born . These caregivers – often women from Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia – have quietly become an essential pillar of support for America’s aging population. They not only fill jobs many domestic workers eschew due to low wages, but studies indicate they often enhance quality of care; for example, nursing homes with higher proportions of immigrant nursing assistants have been shown to deliver better patient outcomes . Yet, even as they hold up our care system, immigrant caregivers frequently toil in the shadows of the economy – undervalued, under-protected, and now, in some cases, under threat. Recent years saw policies that tightened work visas, reduced refugee intakes, and endangered programs like Temporary Protected Status. Such measures risk shrinking the care workforce just as demand is skyrocketing . Providers warn that if immigrants lose legal status en masse, agencies would be forced to cut services or stop accepting new patients , leaving families in the lurch. In short, America’s ability to care for its young and old is deeply entwined with immigration and labor policy.

At the other end of the age spectrum, American families with young children face a parallel crisis in child care. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, affordable quality child care was out of reach for many, and the pandemic’s disruption has pushed the system to a breaking point. The U.S. has yet to establish universal preschool or comprehensive child care support, and parents – especially mothers – often bear the consequences through lost earnings and curtailed careers. The statistics speak to a profound economic strain: a recent analysis found that the infant-toddler child care crisis is now costing the U.S. economy $122 billion in lost earnings, productivity, and revenue every year . This is more than double the estimated cost just five years earlier, illustrating how much the situation has worsened. When parents cannot find reliable, affordable care for their children, they often reduce work hours or drop out of the workforce entirely. Businesses, in turn, lose productivity and incur higher turnover costs. In fact, U.S. businesses lose an estimated $23 billion annually due to child care challenges affecting their workforce, and taxpayers lose another $21 billion in reduced tax revenues, according to the same study. For families, the burden is largest: an estimated $78 billion in forgone earnings and job search costs each year because parents (disproportionately mothers) cut back on work to provide care. These numbers translate to very personal struggles – a mother who foregoes a promotion or a father who works a night shift because daytime child care is unavailable. Nearly three-quarters of U.S. parents with young children report that finding child care is a serious challenge, and over half say it’s a significant challenge to find care that is both affordable and high-quality . The situation has become so acute that experts now refer to it as a “child care crisis” – one that not only hurts families but also threatens future economic growth by pushing parents (especially women) out of the labor force and denying children early learning opportunities.

Compounding these issues is the vast, under-recognized labor of unpaid family caregivers. Millions of Americans – mostly women – are the primary caregivers for an aging or disabled family member, or provide unpaid child care for grandchildren. This unpaid care work, while often a labor of love, carries heavy economic opportunity costs. In 2021, family caregivers in the U.S. provided an estimated 36 billion hours of unpaid care – work that AARP valued at approximately $600 billion if paid at market rates. To put that in perspective, $600 billion is nearly the size of the entire annual defense budget, or about quarter of the total U.S. GDP devoted to care when combined with the paid care sector. This staggering figure represents the silent subsidy that families (again, mostly women) contribute to the economy. But it also represents a vulnerability: if these informal caregivers burn out, cut back hours, or can’t carry on, the cost would shift to health systems, employers, or public programs – none of which are fully prepared to absorb it. Already, we see worrying signs: studies have found that family caregivers often suffer career penalties averaging hundreds of thousands of dollars over their lifetimes in lost wages and retirement benefits, especially women who step out of the workforce for caregiving. The human toll is evident in the stress, health problems, and isolation many caregivers experience. And when overburdened caregivers can no longer provide adequate support, the people they care for – our elders, persons with disabilities, chronically ill family members – may end up in costly institutional care or hospitals. In short, the cracks in America’s patchwork care system are widening: a rapidly aging population, a shrinking care workforce, a child care system on the brink, and an overtaxed network of unpaid caregivers. The result is a growing care gap – one measured not only in emotional anguish and burnout, but in hard economic terms like lost GDP, workforce attrition, and higher medical and social costs.

The Economic Toll of Care Instability

Care is profoundly personal, but when the caregiving system falters, the damage ripples through the broader economy. The instability of care has become a serious economic liability for both the United States and the world. A recent Boston Consulting Group analysis warned that if the U.S. care sector continues on its current troubled trajectory, the country could forfeit $290 billion in GDP by 2030 due to reduced labor force participation and productivity . In a worst-case scenario, the annual hit to GDP could reach $500 billion by 2030 . These losses stem from a simple equation: when adequate care isn’t available, other productive activity suffers. Parents (disproportionately mothers) reduce paid work to care for kids, adult children quit jobs to tend to aging parents, and experienced care professionals leave the field due to low wages, only to be replaced (if at all) by less experienced or temporary staff. The BCG report notes that for every 10 paid caregivers who quit, another person (often a family member) is forced to leave their job to fill the gap – a backfill effect that cascades across industries. Small wonder then that business coalitions and economists are increasingly alarmed about the “care crisis” as a drag on growth and productivity.

Globally, the stakes are just as high. The “care economy” worldwide is enormous – and often undervalued. It includes not just doctors and nurses, but nannies, childcare workers, eldercare aides, domestic workers, and the unpaid labors of love in homes and communities. According to the International Labour Organization, about 381 million people worked in care jobs (paid) in 2018, representing 11.5% of all global employment. But this is just the tip of the iceberg. A far greater number – close to 2 billion people globally – are performing care work unpaid, often as full-time caregivers for family members . If we were to add up all the hours of unpaid care and value them at even a minimum wage, the figures are breathtaking. Women and girls perform 12.5 billion hours of unpaid care work every day across the world. Oxfam estimates that this labor would be worth at least $10.8 trillion per year if monetized – more than three times the size of the global tech industry . The fact that such an astronomical contribution goes unrecognized in GDP calculations is itself telling – care work has been historically taken for granted. But as families and communities struggle, the economic impact is beginning to show. One clear indicator: women’s workforce participation remains significantly constrained by caregiving responsibilities. Worldwide, some 42% of women say they cannot take on paid work because of unpaid care duties, compared to just 6% of men . This “gender care gap” represents a massive loss of talent and income. Entire economies, especially in aging societies, are forgoing growth because half their workforce is hamstrung by inadequate support for care.

Care instability also exacts costs in terms of health and human capital that are harder to quantify but no less real. When children lack stable care or early education, their development can suffer, affecting future productivity. When seniors or people with disabilities cannot access home care, they may experience health declines or require expensive hospitalizations. A recent study calculated the physical and mental health toll of caregiving on caregivers themselves costs the U.S. an additional $264 billion per year in medical expenses and lost productivity. And in extreme cases, care breakdowns can turn into acute crises – as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, when childcare centers closed and nursing homes became epicenters of infection, forcing millions of families into impossible choices. The pandemic was a harsh lesson that care infrastructure is as vital to economic resilience as roads or electricity. Without it, other systems collapse.

It’s also important to recognize how interconnected the global care economy is, and how instability in one region can have spillover effects. For instance, many high-income countries effectively “import” care labor from lower-income countries – whether it’s Filipina nurses in the Gulf states, West African nursing aides in Europe, or Central American nannies in the U.S. These global care chains send billions in remittances back to home countries, supporting families and communities. But they also create dependencies. If migration policies tighten in destination countries (as has happened with shifting immigration rules in the U.S. and UK), labor shortages result, driving up costs of care. Conversely, if economic or political crises erupt in sending countries, the supply of migrant caregivers can suddenly change. The economic contribution of migrant care workers is immense: for example, in many Western European nations facing aging populations, foreign-born caregivers make up over 20% of the long-term care workforce on average. In Italy and Spain, two of Europe’s “oldest” societies – over 60–70% of home care workers are migrants. These workers fill gaps that native-born workers do not, and they often enable high-skilled professionals (particularly women) in the host country to remain in the labor force by caring for their children or parents. Thus, a shortage or instability in this migrant workforce can have a cascade effect on productivity and labor supply in other sectors. It’s a sobering example of how the global economy quietly leans on a foundation of care work, much of it carried out by women across borders.

In raw economic terms, investing in a stable care system yields high returns, while failing to do so incurs heavy costs. Research by McKinsey and others has suggested that closing gender gaps in the workforce (which is not possible without addressing care burdens) could add tens of trillions of dollars to global GDP in coming decades. By contrast, letting care crises fester will sap growth. The World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2023 identified the current worldwide “cost-of-living crisis” fueled in part by care disruptions and labor shortages, as the top short-term threat to global stability. In sum, whether in a small town in the U.S. or across the global economy, the instability of care is not a “social issue” separate from economics, it is directly entwined with productivity, fiscal health, and prosperity. The next section will examine how global upheavals – war, displacement, authoritarian policies are further destabilizing care systems, especially in the Global South, and threatening hard-won gains in human development.

Conflict, Climate and Care: Threats in the Global South

Wars, displacement, and demographic changes mean more older people and children are left without stable care, highlighting the fragile state of global caregiving systems.

The challenges of care are not confined to wealthy nations – low- and middle-income countries across Africa, Asia, and Latin America are grappling with similar dynamics under even more precarious conditions. In many of these countries, formal care services (such as nursing homes, daycares, or community health aides) are sparse; families and informal networks shoulder the bulk of care responsibilities. This traditional reliance on family care worked in the past when younger generations were plentiful and stayed close to home. But demographic and social shifts are eroding those patterns. Urbanization and global migration mean adult children may move far from their elderly parents. Fertility rates are declining in many developing countries too, portending a future where there are fewer young people to care for the old. Africa, for instance, while currently the world’s youngest region, will see its population of older adults (60+) grow more than threefold from 69 million in 2017 to 225 million by 2050. By mid-century, about 10% of Africa’s population will be over 60 (up from just 5% in 2017) – a dramatic aging that few African health and social systems are prepared to support. The World Health Organization warns that the number of older people needing care in developing countries will quadruple by 2050. In countries that still struggle with infectious diseases and child mortality, the issue of eldercare is often called a “crisis hiding in plain sight.” Without proactive policies, millions of elderly could be left without support as the traditional caregivers (their middle-aged children) either migrate or juggle multiple jobs in informal economies.

The Global South’s care systems are being further undermined by the intertwined forces of war, climate change, and authoritarian governance. Conflict and instability have a devastating, immediate impact on caregiving. When war erupts, families are torn apart – many caregivers (typically women) and children flee as refugees, while others (often men, but also many women) may be conscripted or killed. Basic social services like healthcare, schools, and community centers are disrupted or destroyed. Consider the toll of ongoing conflicts: in Ukraine, after the 2022 Russian invasion, more than 8 million Ukrainians (mostly women and children) became refugees practically overnight . This mass displacement has left countless elderly and disabled people behind in war zones without their usual caregivers, and it has also stretched the social services of the countries receiving the refugees. War’s chaos means that continuity of care is shattered – children miss vaccinations and schooling, people with chronic illnesses lose access to medicine, and the elderly who relied on home visits or family support find themselves isolated. In conflict-affected regions of the Middle East and Africa, we’ve seen surges in child malnutrition and maternal mortality as health systems collapse. For example, during Afghanistan’s decades of conflict and especially under the current Taliban regime, maternal and child health indicators have sharply worsened: women’s morbidity and mortality increased when female health workers were banned and clinics shut down . During Taliban rule in the 1990s, prohibiting women from working or studying – including doctors and nurses – “severely affected women’s lives, and undermined the health of the nation’s women and families”. The current return to such policies (e.g. banning midwives and female NGO workers) is already resulting in decreased availability of care and rising complications in childbirth. In a real sense, war and authoritarianism can roll back decades of progress in health and social care overnight, as hospitals are bombed or women professionals are pushed out of service.

Authoritarian and regressive political regimes pose another, sometimes less obvious, threat to care systems and family well-being.

Around the world, a resurgence of strongman politics and anti-democratic trends often goes hand-in-hand with an assault on social policies that support caregivers and women’s rights. In some cases, governments with authoritarian tendencies prioritize military and security spending at the expense of social programs, or they centralize power and siphon resources away from community services. In other cases, they actively undermine gender equality initiatives under the banner of “traditional values.” We have seen examples in various countries: Poland’s populist government slashed funding for the national women’s rights ombudsman and restricted access to emergency contraception , moves that have chilling effects on women’s health and autonomy. Russia under Putin decriminalized certain forms of domestic violence in 2017, sending a message that women’s safety in the home – a fundamental aspect for secure caregiving – is a low priority. In Brazil a few years ago, an administration espousing hyper-traditional roles merged and weakened the ministries that once focused on women’s and human rights . These policy choices share a common thread: they erode the support systems that families, and especially women, rely on to manage care. When reproductive rights are curtailed, or protections against gender-based violence are removed, or civil society groups that assist families are muzzled, the result is more burden on individual households behind closed doors. The “global backlash” against gender equality and family rights has real impacts: it threatens paid maternity leave, childcare programs, and eldercare initiatives, often dismissing them as “western” or unnecessary. As one Freedom House analysis noted, today’s autocrats frequently frame gender equality and care policies as part of a “gender ideology” to be combated . Unfortunately, the victims of this rhetoric are everyday people – the mother who loses a childcare subsidy, the father who cannot take paternity leave, the retiree who sees no increase in meager pension benefits.

Another destabilizing factor is the scale of global migration and displacement, driven by conflict, persecution, and increasingly climate change. The world is witnessing the highest levels of displacement on record: as of the end of 2024, about 123 million people worldwide were forcibly displaced from their homes due to conflict or human rights abuses . This figure includes refugees who have fled abroad and tens of millions of internally displaced within their own countries. Add to that the people uprooted by climate disasters – in 2022 alone, there were over 30 million new internal displacements caused by floods, storms, and droughts, on top of those fleeing violence. Each displaced family represents a care crisis: children separated from caregivers, or thrust into the sole care of one parent; disabled and elderly people left behind or struggling to survive in refugee camps without their usual support network; communities losing the very people (teachers, nurses, community elders) who often provide care. Climate migration is an emerging driver of family separation as well – when livelihoods fail due to crop failure or disaster, often one or both parents migrate to cities or abroad, leaving grandparents or older siblings caring for young ones. For instance, prolonged droughts in parts of sub-Saharan Africa have led to waves of migration, with young men and increasingly young women moving in search of work, while the very old and very young remain in villages with scant resources. This has created “skip-generation” households say, a 70-year-old caring for multiple grandchildren which can be extremely fragile. Climate change also adds direct stress on caregiving: extreme heat and weather disasters disproportionately endanger the elderly, the sick, and children. Without substantial community support or infrastructure (like cooling centers, evacuation plans, or healthcare access), caregivers in poor regions face an almost impossible task of protecting their dependents from climate shocks. The economic impact of these disruptions is profound. When a family member migrates, they might send remittances (global remittances to low- and middle-income countries topped $600 billion in recent years, a lifeline for many families). But the flip side is the social cost: children growing up without parents at home, or elders aging without their adult children’s care. Some countries in the Global South, like the Philippines or Nigeria, train thousands of nurses or domestic workers who then staff the care industries of richer countries, it’s a boon for remittances but a brain drain for local healthcare systems. Eighty percent of African countries are experiencing health worker shortages, and a significant factor is the exodus of nurses and doctors to higher-paying jobs abroad. This creates vicious cycles: a nurse from Kenya cares for elderly patients in London, while her own aging relatives back home struggle for lack of qualified healthcare personnel in their district.

Taken together, these global forces – conflict, climate, and regressive politics are hitting care systems in low- and middle-income countries from all sides. They threaten to reverse the gains made in recent decades in public health, education, and gender equality.

We must remember that the ability of families to care for their members underpins progress in all other areas.

For example, improvements in maternal health and early childhood education in parts of Africa and Asia came about due to deliberate policies (training midwives, creating community childcare, educating girls). War or authoritarian reversals can negate those advances frighteningly fast. The loss is not just social, but economic: a generation of children traumatized by conflict or out of school because their caregivers are displaced will have lower productivity later; societies that marginalize women also forfeit the economic contributions women make when freed from onerous unpaid care burdens. In the next, final section, we will discuss why the converging care crises demand a systemic, coordinated response – and how investing in the care economy is not only a moral imperative but also one of the smartest economic investments societies can make in these uncertain times.

Investing in Care: A Global Imperative

Throughout this exploration, one theme should be clear: caregiving is infrastructure. It is the infrastructure of our daily lives, of our workforce, of our future. Yet it has long been undervalued and patchily supported.

We find ourselves at a crossroads in 2025. The shocks of recent years – a global pandemic, wars in Ukraine and other regions, climate disasters on every continent, democratic backsliding – have exposed just how fragile our care arrangements are. But these crises have also elevated care on the policy agenda like never before. There is growing recognition among entrepreneurs, corporate leaders, policymakers, and even financiers that without a robust care system, economies falter and societies crumble. So what is to be done? The solutions must be as interconnected as the problem, spanning public and private sectors, and international borders.

First and foremost, systematic public investment in the care economy is needed – heavy investment – to create robust, resilient, and equitable care systems. This means treating child care centers, nursing facilities, home care services, and community health workers as essential infrastructure, deserving of funding and support akin to schools, roads, or hospitals. In the United States, this could look like finally enacting policies that the rest of the developed world adopted long ago: national paid family leave, universal pre-K and affordable child care, and better wage support for care workers. It is no coincidence that the U.S. is the only OECD nation without guaranteed paid maternity leave – a policy gap that leaves many families in crisis when a baby is born or a relative falls ill. Addressing this gap would dramatically improve labor force retention for caregivers. There are models to learn from: for instance, Washington D.C.’s universal pre-kindergarten program increased maternal labor force participation by 10 percentage points, by providing reliable early education for every 3- and 4-year-old . Scaling such programs nationally would unleash billions in productivity and give children a stronger start in life. Similarly, raising the wages and professionalizing the career paths of paid caregivers (in child care, home health, etc.) would reduce turnover and improve quality. It’s not just a social nicety – it’s hard economics. A World Economic Forum analysis found that if current trends continue, the U.S. stands to lose hundreds of billions in GDP, but much of that loss could be averted by investing in care and thereby keeping more people (especially women) productively employed .

Globally, countries need to view care as part of the backbone of economic development. International institutions and donors are beginning to emphasize this. The first-ever International Day of Care and Support was observed in 2023, with the ILO and UN calling on governments to channel resources into the care economy and “create robust, resilient and gender-responsive” care systems. For developing countries, this might mean expanding social protection programs that directly support caregivers – for example, cash transfers or pensions for grandmothers raising orphans, or stipends for families caring for members with disabilities. It also means building the workforce: investing in training programs for nurses, midwives, early childhood educators, and community health workers, and crucially, incentivizing them to stay with decent pay and working conditions. The African Union and partners, for instance, are exploring “health workforce bonds” and diaspora programs to bring health professionals where they are needed most . This kind of systemic approach recognizes that you cannot solve healthcare or education without also solving the shortage of caregivers.

Another key piece is international policy coordination on migration and labor. Destination countries that rely on immigrant care workers (which is most advanced economies) should create legal pathways and protections for these workers, essentially treating them as the essential workers they are. This could include special visas for care workers, agreements with source countries that include training and circular migration (so workers can gain skills and perhaps return home if they wish), and bilateral efforts to avoid brain drain by investing in training more personnel than a single country needs. For instance, some countries are considering “global skill partnerships” in nursing, where European countries fund nursing schools in African nations, training extra nurses so that both Europe and Africa benefit. On the flip side, nations facing large refugee flows must include care considerations in their response, for example, ensuring that refugee children can continue schooling and that older or disabled refugees receive appropriate care services. Host communities should be supported in absorbing these populations in ways that strengthen, not overwhelm, local care infrastructure (e.g. funding to expand clinics and hire additional teachers or aides in areas hosting many refugees).

Crucially, respecting women and upholding their rights is central to fixing the care crisis. This is not just about fairness; it’s pragmatic. Women still perform the majority of care work, paid and unpaid. When their rights are curtailed or their opportunities limited, care burdens grow and economies suffer. Conversely, when women’s equality is advanced, care work tends to be more valued and shared. Thus, pushing back against the authoritarian “gender backlash” is part of the solution. Governments (and companies) should actively promote policies like paternity leave – to encourage a more equal sharing of child-rearing – and enforce anti-discrimination laws so that caregivers (who are often women) aren’t penalized at work. Community and grassroots organizations, many led by women, are also key allies in strengthening care systems; they must be supported, not stifled. For example, the National Domestic Workers Alliance in the U.S. campaigns for a Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights to extend labor protections to domestic and care workers . Such efforts, which often come from civil society, need backing through law and resources.

The private sector too has a role to play. Innovative companies are finding that providing care-friendly benefits is not just altruism but good business. Employers that offer on-site child care, flexible schedules, or subsidies for eldercare find higher retention and productivity among staff . In tight labor markets, care benefits can be a competitive edge in attracting talent. Corporate leaders can also invest in care infrastructure via public-private partnerships – for instance, co-funding community childcare centers or training programs for caregivers. There is also room for social entrepreneurship: new startups are emerging to match caregivers with families, provide tech-enabled respite services, or deliver community-based eldercare solutions in creative ways. Such innovation should be encouraged with funding and an enabling regulatory environment, as part of a wider ecosystem of care solutions.

Finally, recognizing and respecting care work is an essential cultural shift that underpins policy changes. As a society, we must embrace a “care mindset” that treats care as foundational, not peripheral. This includes measuring what matters – incorporating care work into economic indicators and planning. (New Zealand, for example, has experimented with “well-being budgets” that explicitly consider care and mental health outcomes in fiscal policy.) It also means listening to caregivers and care recipients in designing policies. Too often, those making policy have never had to change an adult diaper at 3 AM, or console a colicky baby through the night and then work a full day. Bringing those lived experiences into policy deliberation leads to more humane and effective solutions.

The instability of caregiving systems is one of the defining challenges of our era, intersecting with virtually every major global issue, from labor markets to migration, from gender equality to economic growth. The cost of inaction is high: measured in lost dollars, yes, but more poignantly in lost human potential and fractured communities. Conversely, the benefits of action are enormous. Research and real-world examples show that investing in care pays off: it creates jobs (often green, non-outsourcable jobs), boosts consumption and tax revenues (as more people can work), and improves outcomes for children and elders. Perhaps most importantly, it enhances the well-being and dignity of people – the very fabric that holds societies together. As UN Secretary-General António Guterres has pointed out, a new generation of social protection and care systems is needed to uphold dignity and opportunity for all in a world of turbulence . It is time for leaders at all levels – from the CEO considering a new family leave policy, to the lawmaker drafting a care infrastructure bill, to the international donor funding post-conflict recovery – to recognize care as the bedrock of resilience.

Remember that mother in Ohio? The caregiver in New York? The grandmother in Africa? Those situations do not have to end in crisis. With thoughtful policy and investment, we can write a different story: one where a robust support system catches the mother when daycare falls through, where the immigrant caregiver is valued and enabled to stay, and where the African grandmother’s community has the resources to help her raise the next generation. In a world rife with authoritarian challenges, wars, and climate upheavals, strengthening caregiving systems is both an economic necessity and a lifeline. It is, in the end, an affirmation of our common humanity: that we look after one another, in good times and bad, and that we build economies that do the same.

Blessing Oyeleye Adesiyan is a chemical engineer, the Editor-In-Chief at The Care Gap, and the Founder & CEO of Caring Africa. She leads advocacy, platform innovation, and policy design to formalize the care economy in the United States, Nigeria, and across the globe. A mother of four and former Fortune 100 executive, she brings lived experience and technical expertise to drive care-forward solutions for families, women, and economies globally.